What Makes a Customer? In Short, Income.

They're essential to all businesses, the life blood of the economy, but what exactly turns a person into a customer? It turns out, having a job may be the most important thing.

We’ve all done it. We all know what it’s like. The feeling of handing over some bills, swiping a card, or nervously signing your name to a credit agreement. All in exchange for some shiny trinket or a trip around the sun; But what exactly happens in the process of becoming a customer? Were you one last week? Will you be one next week? What exactly changes in between?

Before we start breaking things down please grant me that we’re talking about people here. Their financial and personal situations, fears, whims, desires, and perceptions of the world. All told, it’s mushy, there won’t be clear lines as to who spends and who doesn’t but in broad terms I think we can agree on some key elements that should be considered no matter how generalized.

At a very base level, to be a customer one must be able to make a purchase and want to make a purchase. In other words:

A Customer = One who both possesses purchasing power, and decides that a decrease of that Purchasing Power is an Acceptable Trade for a certain good or service.

Embedded here are some situations we’re all aware of. The higher the price (i.e. the greater the loss of purchasing power), the more we need to get out of the deal. Just bought a new car? You’re probably not buying another one anytime soon (i.e. the need or want is greatly diminished). For those reasons I’d like to keep this article focused on being a customer writ large, not someone after an individual item, but in general someone with a propensity to spend.

In the above definition of “A Customer” there are two things that we need to take apart further. One straightforward, one not so much.

Purchasing Power = Money one can use to pay now (cash) or money one can use to pay later (credit).

Cash or credit, that’s really it. If you want to muddy the water with barter, servitude, theft, etc. be my guest, but we’re trying to generalize things here. We will revisit the idea of credit later.

Acceptable Trade = The pros outweigh the cons.

And this is where the human side comes in. We all weigh factors relating to finances and spending differently, and for good reason.

The pros of a purchase lie somewhere on a continuum between satisfying the most basic of needs (food, water, shelter) i.e. “necessities” and what can only be considered luxuries (first class vs economy, rib eye over sirloin, ad-free YouTube) i.e. “discretionary spending”. This mix of need, desire , status, pleasure, or comfort is ultimately how we judge the benefits of spending money.

I would also argue that this mix is slow to change. Over time you may worry less about wearing the latest fashion, or learn that life is too short….have desert; But these occur over years, and if one is trying to judge who becomes a customer in the near future you are safe to ignore potential changes in desire. Equally, this mix is independent of one’s financial situation. One may trade-down to the sirloin or tolerate a few YouTube ads to save a few dollars when times feel lean, but the innate preference remains. Again, in the short term, you’re safe to assume these desires are static.

This is important because if we fix the pros side of the acceptable trade equation the driving variable becomes the cons involved; And how they change over time influences who is a customer and who is not.

So what are the downsides of making a purchase? The most obvious; One now has less money or owes more money in the future. Another common downside, upkeep. A new car will need insurance, tires, oil changes. A new home, landscaping, and a water heater every several years. In other words, and similar to the prior, owing more money in the future.

There are of course other cons to a purchase. More clutter in an already packed closet, figuring out what to do with two dozen Amazon boxes weekly, fear of spoiling your children; But these more tangential cons, like the pros discussed prior, tend to carry the same weight over time. Again, a variable we can safely ignore.

In the end, the amount of money one has or the amount of money one owes in the future will drive the cons side of the purchase equation.

Yes, but the amount of money one has today or the amount of money one owes in the future do not reside in a vacuum. Their absolute values tell us little, they need to be compared to one’s overall financial situation. Mainly:

Upcoming expenses, future obligations.

Upcoming income, money to replace that which was spent prior or to pay that which is owed.

Once again, everyone finds themselves in a different situation. Some are flush with cash, extraordinarily wealthy and the expenses they have in the future pale in comparison to the money they have today. Good for them, they will always be customers; And while their appetite for artwork and French villas may wax or wane with the Dow Jones average, the bulk of their everyday consumption will continue on. The financially wealthy are, almost by definition, the minority. The majority find themselves in need of future income to maintain their current lifestyle and meet future obligations.

So to summarize things a bit, the pros of making a purchase as well as some cons are slow to change, meaning if want to look at what turns someone from a non-customer to a customer in the short term we best focus on the remaining cons of a purchase. These are more fluid, impactful, and chiefly:

How much money does one have today (cash)

How much money will one need in the future (expenses, credit payments)

How much money will one gain in the future (income)

Without going on too much of a tangent, the above should demonstrate why inflation is so taxing on most people. Incomes are likely fixed in the near term, while the true value of cash on hand today decreases, and the cost of future expenses increases as prices rise.

To break these items down a bit further:

How much money does one have today (cash)

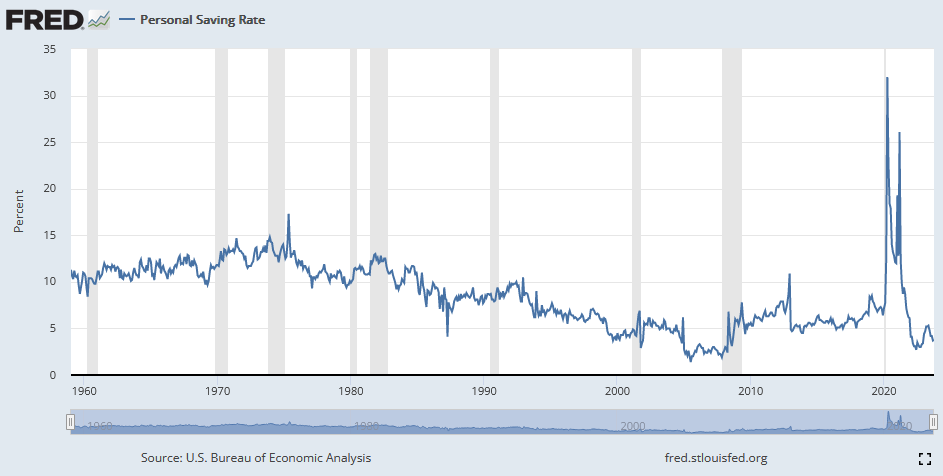

Savings, is the simpler term for this amount; And while everyone would be OK with greater savings, a level that brings comfort (and thus increased willingness to spend) is likely determined by the bullet points that follow for most people. Of course, this level may not be achievable depending on circumstances, and history reflects how variable the savings rate is over time (see image below).

How much money does one need in the future (expenses, credit payments)

In the near term expenses for individual items (a loaf of bread, utilities, mortgage, insurance) are relatively fixed. What is more dynamic is the number of future obligations one commits themselves to (a 2nd car, Netflix and Hulu, another pet).

Credit payments, quite simply are a function of the amount owed (obligations taken on) and the interest rate on those obligations. The amount of debt goes up, interest rates go up, credit payments go up. The opposite also being true.

How much money will one gain in the future (income)

For the majority of people, particularly ones prone to variable spending habits, income means being employed. Thus, “how much money will one gain in the future?”, is really “will I have a (good paying) job in the future”.

To return to our earlier question. What makes for an acceptable trade? When do the pros outweigh the cons of a purchase? Based on the above I would posit that:

A purchase of true necessity occurs every time it is needed unless both savings and access to credit are exhausted.

A discretionary purchase occurs when one feels confident enough in their amount of current savings and future income.

In other words when one feels good about the amount of money they have today and their ability to replace it in the future, discretionary purchases occur.

The word “feel” here is important as it is very subjective and very human. We all know the penny-pinchers in our life as well as those that never let tomorrow get in the way of today. The fact that we notice them though means they are likely outliers. The majority of people are out there making somewhat reasonable decisions about purchases and their finances.

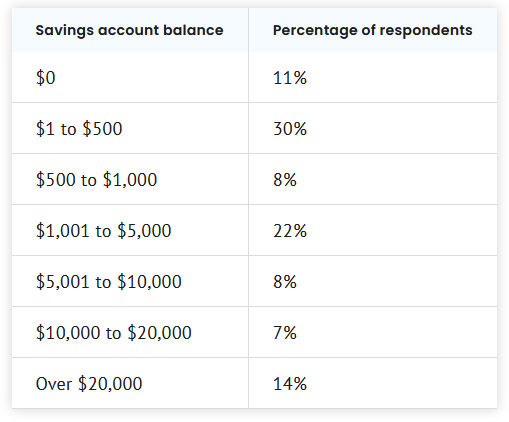

Unfortunately the majority can’t feel too great about the amount of money they have in the present. In the summer of 2023 The Motley Fool polled Americans about their savings account balances.

https://www.fool.com/the-ascent/research/average-savings-account-balance/

The table below summarizes their findings.

With the median US salary being approximately $4,000 per month, only 30% of respondents likely have more than one month’s salary in savings. Said another way, purchasing decisions for 70+% of Americans are surely driven by confidence in future income. For most this means, will I have a (good paying) job next month?

This shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise as one’s ability to earn a living is often their greatest asset (particularly for the young). In economics the term “wealth effect” is often used to describe one’s confidence to spend when their house is worth more or their stock portfolio is up. For the 35% of Americans who don’t own a home, the 40% who don’t own stocks, and the likely far greater amount that don’t have significant savings in either the “wealth effect” is how much they can get for their time and labor.

Of course, when someone else if feeling confident about your ability to earn an income in the future that creates additional means to make a purchase. Credit.

If you recall, earlier it was stated:

Purchasing Power = Money one can use to pay now (cash) or money one can use to pay later (credit).

Having considered the variables of having money now (cash) and the decisions to spend said money. Let’s turn briefly to the availability of credit.

Most people, and acknowledging there are outliers, want to repay money they borrow. Thus, before borrowing money, one needs to feel confident they can repay that amount in the future. In other words, and as stated prior, they feel confident that income in the future will be there to meet all their obligations. As deduced earlier, for most this means does one have a job, will one have a job.

Accessing credit requires confidence by two parties though. The lender, who parts with money now for the promise of additional money in the future (principal + interest); and the borrower, who agrees to pay a larger sum in the future for access to a smaller sum in the present.

To oversimplify the thought process of lenders, they will work through the following when making a loan:

How much am I lending and for how long?

To whom am I lending and how confident am I that they can pay it back?

How much does it cost me to get the money to lend? (i.e. the current short term interest rate)

What is my opportunity cost with this money? (i.e. could I get a better risk-adjusted return elsewhere)

What amount of money do I need to have returned to me in the future to offset the risk that I may not be paid back? (i.e. the interest rate on the loan)

Thus for a borrower it’s easier to borrow a small amount, for a short period of time, when the lender has high confidence you will pay it back. It is cheaper to borrow (i.e. the gap between what you get now and what you pay in the future is smaller) when short-term interest rates are low, risk-free rates are low (typically United States T-Bills or Bonds), and when the lender has high confidence you will pay it back (i.e, the lender needs a smaller premium above the risk-free, or opportunity cost rate to make the loan).

I put the word “confidence” in bold as it appears twice in the above. It is tied to both the ease of obtaining credit, and the cost of obtaining credit. So what gives a lender confidence in a borrower? Turns out the it’s the same as what entices a borrower to borrow and spend:

Cash, savings on hand now.

Future income minus future obligations.

And what are these correlated with? Having income today, reasonable future obligations, and a high likelihood of income in the future; And as discussed, for most people this translates to, having a job today and a high likelihood of having a job tomorrow.

It seems to becoming clear that having income (i.e. a job) is the chief factor in one becoming and staying a customer. That both the decision for an individual to spend and the decision for a lender to extend credit to a borrower are heavily influenced by the employment status of the individual.

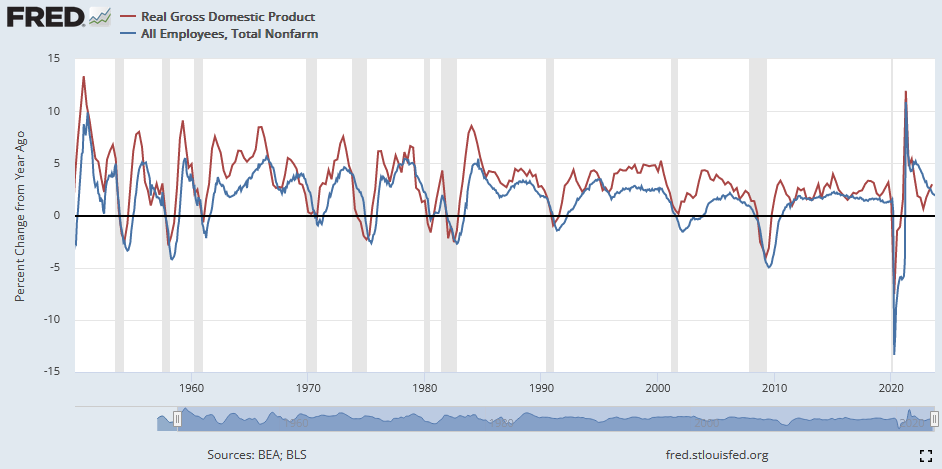

If one takes a historical look the idea that the economy grows faster as more people become employed seems to have a lot of support; And if you recall every business needs customers.

As a final note, in the question of what makes a customer, access to (affordable) credit is hard to overstate. For reasons discussed above, very few are able to purchase large-ticket items (new cars, a home, funds to start a business) without leveraging their future income to gain access to the necessary money today. Without credit, they wouldn’t be a customer. Thus, the more available credit is and the lower the rate of interest, the more customers the economy has for larger purchases.

So what makes a customer? Income, a job (and credit doesn’t hurt).

Please let me know any comments you have. I write these posts to refine my own thought process and welcome the input of others. I also hope soon to publish post tying the above dynamics of customer growth to the business cycle and why I feel a recession in 2024 is more likely than not.

kinda like the fun one has while painting, and finds themselves painted in? or not at all?